How do I build a Network Layer

Working and leading two projects at a time means a great opportunity to experiment with app architecture, and do experiments with other concepts I had in mind or just learned and wanted to try them out. One of topics I learned recently and I think you might find it useful if how I build a network layer now.

Nowadays mobile apps are client-server oriented, so pretty much there is a network layer somewhere in the app, smaller or bigger. I saw many implementations to date but every had some drawbacks. Not thinking the latest one I build has no drawbacks, but it seems to work very well in two projects I am working on currently. And has test coverage close to 100%.

In this article we’ll cover network layer that talks only with one backend, sending JSON encoded requests, so not that complex. The layer will talk with AWS later on and send some files there, but it should be easy to extend its functionality to do so.

Thinking process

Here are some questions I like to ask myself before building such a layer.

- Where to put the code that have knowledge about the backend url?

- Where to put the code that knows about the endpoints?

- Where to put the code that knows how to build a request?

- Where to keep all the code that cares about preparing parameters for a request?

- Where should I store authentication token?

- How to execute requests?

- When and where to execute requests?

- Do I care about cancelling requests?

- Do I need to care about wrong backend responses? Some backend bugs?

- Do I need to use 3rd party frameworks? What frameworks should I use?

- Is there any core data stuff passing around?

- How to test the solution?

Storing backend url

First of all, where should I put the backend url? How other piece of the system

will know where to send requests? I prefer to create a BackendConfiguration class

that stores such information.

import Foundation

public final class BackendConfiguration {

let baseURL: NSURL

public init(baseURL: NSURL) {

self.baseURL = baseURL

}

public static var shared: BackendConfiguration!

}Easy to test, easy to configure. You can set the shared static variable and

access it wherever you want in your network layer, no need to pass it everywhere.

let backendURL = NSURL(string: "https://szulctomasz.com")!

BackendConfiguration.shared = BackendConfiguration(baseURL: backendURL)Endpoints

That’s the topic I experimented with for a while before I found a ready-to-go

solution. Tried hardcoding endpoints while configuring NSURLSession, tried

some dummy Resource-like objects that knows about the endpoint and can be easily

instantiated and injected, but it was still not what I was looking for.

I came up with idea to create *Request object that knows which endpoint to hit,

what method to use, should it be GET, POST, PUT or different, how to configure

the body of a request and what headers to pass.

This is what I came up with

protocol BackendAPIRequest {

var endpoint: String { get }

var method: NetworkService.Method { get }

var parameters: [String: AnyObject]? { get }

var headers: [String: String]? { get }

}A class that implements the protocol is able to provide a basic informations

that are required to build a request. The NetworkService.Method is just an enum

with GET, POST, PUT, DELETE cases.

An example request that maps an endpoint might look like this

final class SignUpRequest: BackendAPIRequest {

private let firstName: String

private let lastName: String

private let email: String

private let password: String

init(firstName: String, lastName: String, email: String, password: String) {

self.firstName = firstName

self.lastName = lastName

self.email = email

self.password = password

}

var endpoint: String {

return "/users"

}

var method: NetworkService.Method {

return .POST

}

var parameters: [String: AnyObject]? {

return [

"first_name": firstName,

"last_name": lastName,

"email": email,

"password": password

]

}

var headers: [String: String]? {

return ["Content-Type": "application/json"]

}

}To not create the dictionary for headers everywhere we can define extension for

BackendAPIRequest.

extension BackendAPIRequest {

func defaultJSONHeaders() -> [String: String] {

return ["Content-Type": "application/json"]

}

}The *Request class takes all the parameters needed to make a successful request.

You’re always sure that at least all the parameters you need will be passed, otherwise you can’t

create a request object.

Defining endpoint is easy. If there should be some id of an object that should be included in the endpoint it is super easy to add it because you actually would have such id stored as a property.

private let id: String

init(id: String, ...) {

self.id = id

}

var endpoint: String {

return "/users/\(id)"

}The method of the request never changes, the parameters body is easily constructed and very easy to maintain, headers too. Everything is very easy to test.

Executing the request

Do I need any 3rd party frameworks to communicate with the backend?

I see that people are using AFNetworking (Objective-C) and Alamofire for Swift.

I used it many times, but for some time I am not using it. Since we’ve got NSURLSession

that do its job very well I don’t think you need any 3rd party framework.

IMO this dependency is going to make your app architecture more complex.

The current solution consists of two classes - NetworkService and BackendService.

-

NetworkService- allows you to execute HTTP request, it incorporatesNSURLSessioninternally. Every network service can execute just one request at a time, can cancel the request (big advantage), and has callbacks for success and failure responses. -

BackendService- (Not the coolest name ever but fits quite well) is the class that takes requests (*Requestobjects described above) related to the backend. It usesNetworkServiceinternally. In the current version I am using, it tries to serialize the response data to json usingNSJSONSerializer.

class NetworkService {

private var task: NSURLSessionDataTask?

private var successCodes: Range<Int> = 200..<299

private var failureCodes: Range<Int> = 400..<499

enum Method: String {

case GET, POST, PUT, DELETE

}

func request(url url: NSURL, method: Method,

params: [String: AnyObject]? = nil,

headers: [String: String]? = nil,

success: (NSData? -> Void)? = nil,

failure: ((data: NSData?, error: NSError?, responseCode: Int) -> Void)? = nil) {

let mutableRequest = NSMutableURLRequest(URL: url, cachePolicy: .ReloadIgnoringLocalAndRemoteCacheData,

timeoutInterval: 10.0)

mutableRequest.allHTTPHeaderFields = headers

mutableRequest.HTTPMethod = method.rawValue

if let params = params {

mutableRequest.HTTPBody = try! NSJSONSerialization.dataWithJSONObject(params, options: [])

}

let session = NSURLSession.sharedSession()

task = session.dataTaskWithRequest(mutableRequest, completionHandler: { data, response, error in

// Decide whether the response is success or failure and call

// proper callback.

})

task?.resume()

}

func cancel() {

task?.cancel()

}

}class BackendService {

private let conf: BackendConfiguration

private let service: NetworkService!

init(_ conf: BackendConfiguration) {

self.conf = conf

self.service = NetworkService()

}

func request(request: BackendAPIRequest,

success: (AnyObject? -> Void)? = nil,

failure: (NSError -> Void)? = nil) {

let url = conf.baseURL.URLByAppendingPathComponent(request.endpoint)

var headers = request.headers

// Set authentication token if available.

headers?["X-Api-Auth-Token"] = BackendAuth.shared.token

service.request(url: url, method: request.method, params: request.parameters, headers: headers, success: { data in

var json: AnyObject? = nil

if let data = data {

json = try? NSJSONSerialization.JSONObjectWithData(data, options: [])

}

success?(json)

}, failure: { data, error, statusCode in

// Do stuff you need, and call failure block.

})

}

func cancel() {

service.cancel()

}

}As you can see the BackendService can set authentication token in headers.

The BackendAuth objects is a simple storage that stores the token in NSUserDefaults.

If that would be necessary it could be storing the token in Keychain.

The BackendService takes BackendAPIRequest as a parameter of request(_:success:failure:)

method and extracts necessary informations from the request object. This is nicely encapsulated

and backend service just consumes what it gets.

public final class BackendAuth {

private let key = "BackendAuthToken"

private let defaults: NSUserDefaults

public static var shared: BackendAuth!

public init(defaults: NSUserDefaults) {

self.defaults = defaults

}

public func setToken(token: String) {

defaults.setValue(token, forKey: key)

}

public var token: String? {

return defaults.valueForKey(key) as? String

}

public func deleteToken() {

defaults.removeObjectForKey(key)

}

}Both NetworkService, BackendService and BackendAuth are easy to test

and maintain.

Queueing requests

Several questions to cover here. What way would we like to perform network requests? What if we want to perform many requests at a time? How would we like to be notified about the success or failure for requests in general?

Decided to go with NSOperationQueue and NSOperations that execute network

requests.

So, I subclassed NSOperation and overrided its asynchronous property to return

true.

public class NetworkOperation: NSOperation {

private var _ready: Bool

public override var ready: Bool {

get { return _ready }

set { update({ self._ready = newValue }, key: "isReady") }

}

private var _executing: Bool

public override var executing: Bool {

get { return _executing }

set { update({ self._executing = newValue }, key: "isExecuting") }

}

private var _finished: Bool

public override var finished: Bool {

get { return _finished }

set { update({ self._finished = newValue }, key: "isFinished") }

}

private var _cancelled: Bool

public override var cancelled: Bool {

get { return _cancelled }

set { update({ self._cancelled = newValue }, key: "isCancelled") }

}

private func update(change: Void -> Void, key: String) {

willChangeValueForKey(key)

change()

didChangeValueForKey(key)

}

override init() {

_ready = true

_executing = false

_finished = false

_cancelled = false

super.init()

name = "Network Operation"

}

public override var asynchronous: Bool {

return true

}

public override func start() {

if self.executing == false {

self.ready = false

self.executing = true

self.finished = false

self.cancelled = false

}

}

/// Used only by subclasses. Externally you should use `cancel`.

func finish() {

self.executing = false

self.finished = true

}

public override func cancel() {

self.executing = false

self.cancelled = true

}

}Next, because I want to use the BackendService for executing network calls

I subclassed NetworkOperation and created ServiceOperation.

public class ServiceOperation: NetworkOperation {

let service: BackendService

public override init() {

self.service = BackendService(BackendConfiguration.shared)

super.init()

}

public override func cancel() {

service.cancel()

super.cancel()

}

}The class creates BackendService internally so I don’t need to create it

in its every subclass.

Here is how the Sign In operation might look like:

public class SignInOperation: ServiceOperation {

private let request: SignInRequest

public var success: (SignInItem -> Void)?

public var failure: (NSError -> Void)?

public init(email: String, password: String) {

request = SignInRequest(email: email, password: password)

super.init()

}

public override func start() {

super.start()

service.request(request, success: handleSuccess, failure: handleFailure)

}

private func handleSuccess(response: AnyObject?) {

do {

let item = try SignInResponseMapper.process(response)

self.success?(item)

self.finish()

} catch {

handleFailure(NSError.cannotParseResponse())

}

}

private func handleFailure(error: NSError) {

self.failure?(error)

self.finish()

}

}In the start method the service executes request that is created internally in

the operation’s constructor. handleSuccess and handleFailure methods

are passed as a callbacks for request(_:success:failure:) method of a service.

IMO this makes the code more clean, and it is still readable.

Operations are passed to a NetworkQueue object that is a singleton and can

queue every operation. For now I keep it as simple as possible:

public class NetworkQueue {

public static var shared: NetworkQueue!

let queue = NSOperationQueue()

public init() {}

public func addOperation(op: NSOperation) {

queue.addOperation(op)

}

}What are advantages of executing operations in one place?

- Easily cancellation of all network operations.

- Cancellation all operations that are downloading images or other operations that are requesting data that is not needed to provide user a basic experience of using the app while network connection is weak. E.g. you would like to prevent downloading images when user is on weak connection.

- You can build a priority queue and execute some requests first to get answer faster.

Working with Core Data

This is the aspect for which I had to delay the publication of this entry. In previous version of the network layer operations returned Core Data objects. The response was received, parsed and converted to Core Data object. This solution was far from ideal.

- The operation have to know what Core Data is. Because I had model detached to separate framework and network layer was in separate framework too, the network framework have to know about model framework.

- Each operation have to take additional

NSManagedObjectContextparameter to know which context it should operate on. - Each time the response was received and was about to call success block it first tried to find object in a context, or hit the disk to fetch object from disk. IMO this is a big disadvantage. You not always want to create Core Data object.

So I came with idea to take out Core Data out of network layer completely. I created middle layer that are objects created in result of parsing responses.

- This way the parsing and creating objects is quick and not require to hit a disk.

- You also don’t need to pass

NSManagedObjectContextto operation. - You can update your core data object in the

successblock using the parsed item and reference to Core Data object that you probably keep somewhere where you create the operation - this is my case in most situations when the operation is added to a queue.

Mapping responses

The idea of response mappers was to separate the logic of parsing and mapping JSON to useful items.

We can distinguish two type of parsers. The first type return just a single object of specific type. The second type is a parser that parses array of such items.

First, let’s define a common protocol for all the items:

public protocol ParsedItem {}Now, here are some objects that are products of mappers:

public struct SignInItem: ParsedItem {

public let token: String

public let uniqueId: String

}

public struct UserItem: ParsedItem {

public let uniqueId: String

public let firstName: String

public let lastName: String

public let email: String

public let phoneNumber: String?

}Let’s define an error type that will be thrown when something went wrong with parsing.

internal enum ResponseMapperError: ErrorType {

case Invalid

case MissingAttribute

}Invalid- thrown when passed json is nil and should not be nil, or when it is array of objects instead of expected json with a single object.MissingAttribute- self explanatory, when key is missing in json or when after parsing the value is nil and should not be.

A ResponseMapper may look like this

class ResponseMapper<A: ParsedItem> {

static func process(obj: AnyObject?, parse: (json: [String: AnyObject]) -> A?) throws -> A {

guard let json = obj as? [String: AnyObject] else { throw ResponseMapperError.Invalid }

if let item = parse(json: json) {

return item

} else {

L.log("Mapper failure (\(self)). Missing attribute.")

throw ResponseMapperError.MissingAttribute

}

}

}It takes an obj which is response from the backend - a JSON in our case,

and a parse method which consumes this obj and returns A object that

conforms to ParsedItem.

Now that we have this generic mapper we can create concrete mappers. Let’s take a look on a mapper used for parsing response of Sign In operation.

protocol ResponseMapperProtocol {

associatedtype Item

static func process(obj: AnyObject?) throws -> Item

}

final class SignInResponseMapper: ResponseMapper<SignInItem>, ResponseMapperProtocol {

static func process(obj: AnyObject?) throws -> SignInItem {

return try process(obj, parse: { json in

let token = json["token"] as? String

let uniqueId = json["unique_id"] as? String

if let token = token, let uniqueId = uniqueId {

return SignInItem(token: token, uniqueId: uniqueId)

}

return nil

})

}

}The ResponseMapperProtocol is a protocol to be implemented by concrete mappers

so they share the same method for parsing response.

Then, such a mapper is used in a success block of an operation and you can operate on concrete object of specific type instead of dictionary. Easy to use such object later, evertything is easy to test.

The last thing is a response mapper for parsing arrays.

final class ArrayResponseMapper<A: ParsedItem> {

static func process(obj: AnyObject?, mapper: (AnyObject? throws -> A)) throws -> [A] {

guard let json = obj as? [[String: AnyObject]] else { throw ResponseMapperError.Invalid }

var items = [A]()

for jsonNode in json {

let item = try mapper(jsonNode)

items.append(item)

}

return items

}

}It takes a mapping function and return array of items if everything is correctly parsed.

Depends on what you expect you might throw an error if just a single item can’t be parsed

or return empty array in worst case as a product of this mapper.

The mapper expects that the obj (response from the backend) is an array of

JSON elements.

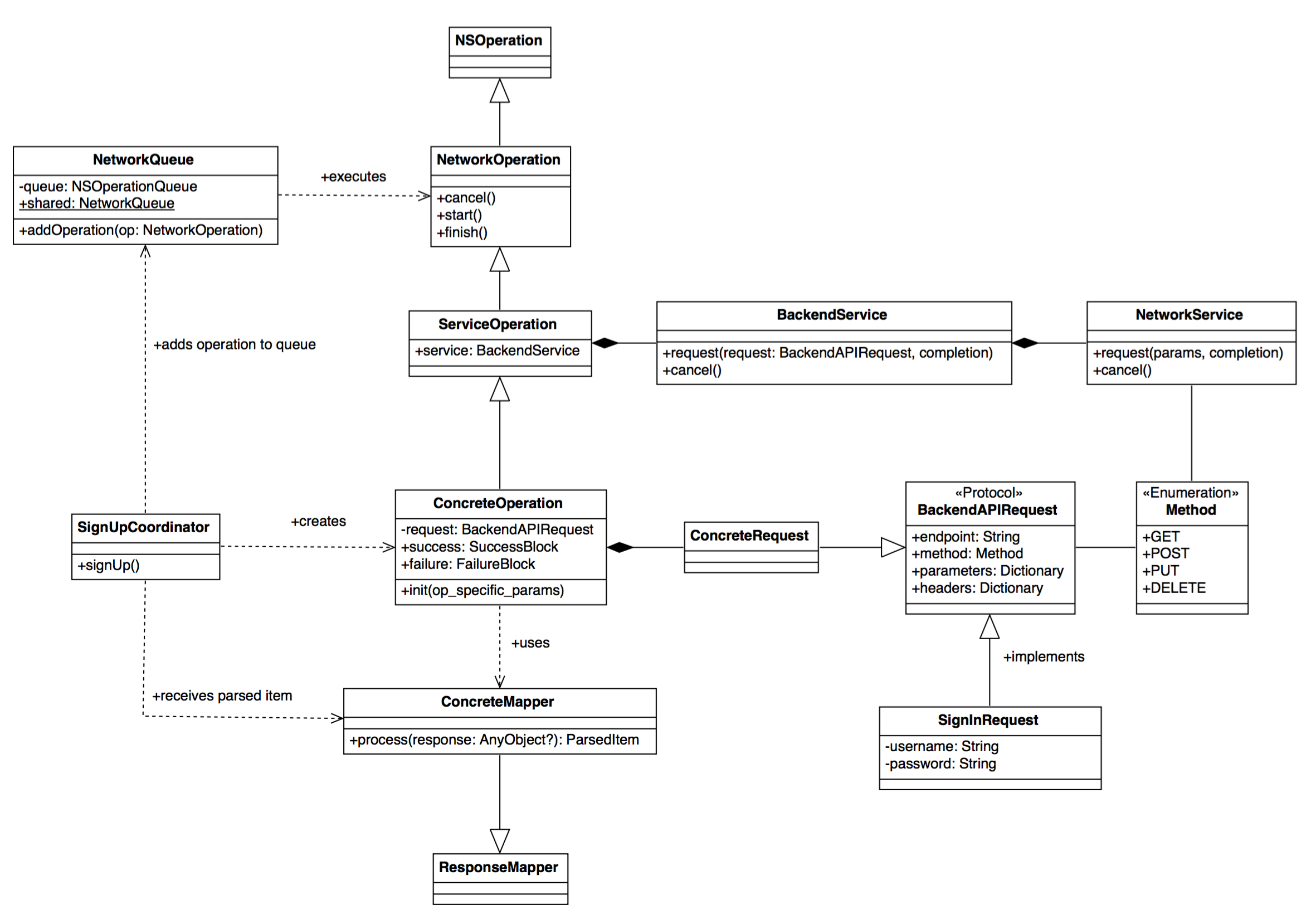

Here is diagram that presents the network layer architecture.

Example project

You can find an example project here on my github. The project is using fake url for the backend, so no request will finish with success. I made this available only to give you a view of how the foundation of the network layer look like.

Wrap up

I found this way of doing network layer very useful, simple and easy to work with.

- The biggest advantage of it is that you can easily add new operations that will have similar design to others and that it does not know anything about Core Data.

- You can keep the code coverage close to 100% with no big effort, without thinking how to cover a super hard cases, because there is no such cases at all.

- The core of it is easy to reuse in other applications that have similar complexity.